|

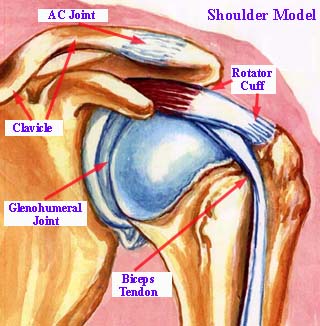

Shoulder Joint AnatomyLet’s talk about shoulder joint anatomy. As we briefly discussed on the introductory page, it is a ball and socket joint configuration.

The humeral head is the “ball" and the glenoid is the “socket”. Other structures that serve to make up the “shoulder girdle” include the clavicle (collar bone), the acromion (top part of the scapula, or, shoulder blade) and the coracoid process (part of the front portion of the glenoid and an attachment point for ligaments).

The sub-acromial bursa sac, which has a reputation for being a troublesome character can become severely inflamed and restrict motion when part of a condition called shoulder impingement

You can also see how the combination of these muscles, tendons and ligaments work together to not only stabilize the joint, but to provide a wide range of functions and movements.

The glenoid (socket) is, by nature, quite shallow, so a structure surrounds it, called the glenoid labrum, which acts to help “deepen” the socket to increase stability. This labrum is the source for several types of injuries that can affect shoulder stability, such as the labral tear, and a condition known as the S.L.A.P. tear. More on that later...

Leave Shoulder Joint Anatomy; return to Shoulder Pain

|

"We hope you enjoy your journey through Bone and Joint Pain.com"